We’ve all been guilty of loving something purely for the aesthetic. Or maybe the concept, if not the execution. Or the characters, but not the plot. Or vice versa. Or maybe we love it because it’s so intricate, it’s actually frustrating.

Sometimes, all you need from a story is a kick in the imagination box, and your brain does the rest. Other times, you exit a world flummoxed, but still undeniably pleased with what you’ve experienced. Sometimes coherence is over-rated. Here are some stories that fill us with wonder… even when we’re not entirely sure what’s going on.

Cloud Atlas by David Mitchell

Honestly, this applies to both the book and the 2012 film adaptation. While it is a truly brilliant exercise, Cloud Atlas asks a lot of its audience, forcing them to balance multiple time periods, a structure that runs forward and then backward chronologically, and a reincarnated protagonist. (The only indication of that plot point is a birthmark shared by each reincarnation, oddly enough.) Cloud Atlas is not an indiscernible story, but it is so layered that it may require multiple reads, or viewings, to swallow up every bit and piece that make the narrative so delicious. Each protagonist, each time period, teaches us something about humanity and the flow of time. While each central character in the novel has a very different journey, they are all ultimately bound by a desire to impart truth into the world, by actions, testimony, music, and so on. Each of them experiences how people do wrong to other people, and it is this understanding that binds their experiences into a single tale.

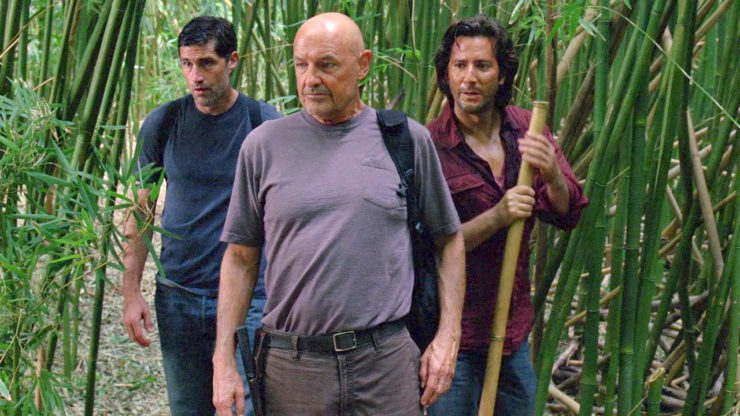

LOST

The island is a metaphor, right? Is it? What is it a metaphor for? Wait, the island is purgatory. No, the island is hell? No, it’s none of those things. But the smoke monster is the devil, or pure Evil? Why do time travel and alternate timelines suddenly become a thing? And what the heck is a Dharma Initiative? You can move the island by turning a wheel? Fans spent years dissecting this show as it was airing, but all the theorizing in the world couldn’t really make sense of all the threads. For some, that kinda ruined the experience, but for many, that was part of LOST’s charm—a journey so complex, you could never truly understand the entirety of it. As part of the mega shift in serialized television towards season-long arcs, the early attempts were bound to wobble a bit, and that was part of what made the show exciting.

Annihilation / Southern Reach trilogy by Jeff VanderMeer

Area X is a terrifying place that can only be survived by people who are… weird enough to handle it. At least, that seems to be what Annihilation (and the rest of the Southern Reach trilogy for that matter) posits. The biologist of the 12th expedition to the region quickly discovers that the psychologist in charge of her group means to control them all with hypnotic suggestion, but she is immune due to inhaling some spores that cause her to glow. Area X seems to absorb people into its makeup; after some time there, the biologist becomes convinced that her husband—who she initially believed had died after making it home from the previous expedition—never made it back, and exists somewhere among the flora and fauna. Will she become a creature, too? And how does that even… work? While there are plenty of science fiction stories that warn us of the terror of space, the strangeness of physics, there are fewer that demonstrate the sheer terror of biology and nature the way that Annihilation do.

Interstellar

Can you interact with the past via a black hole? Christopher Nolan seems to think so, and who are we to argue? The entirety of Interstellar rests of theories of time dilation close to a black hole, resulting in astronaut Joseph Cooper staying the same age while his daughter and everyone on Earth grow older and older. Eventually, Cooper ejects himself into a black hole to give his cohort the chance to make it to the next world they’re tasked with exploring—the result is his arrival in a tesseract of sorts, though we don’t really know if it’s part of the space or created by future humans? Once inside the tesseract, he ends up traveling in time to a point before he left Earth, and realizes that he’s the person who created anomalies in his daughter’s bedroom using gravity. It’s a paradox that leads him to Professor Brand and the mission in the first place. When he comes out of the tesseract, he finds that his daughter solved the problems with the first plan to evacuate humanity from the Earth, and now everyone is living on a colony above Saturn. The point is, time is meaningless but love endures. At least, that’s probably the point.

Malazan Book of the Fallen by Steven Erikson and Ian C. Esslemont

The Malazan series can be difficult to follow because it spans thousands of years, is utterly meticulous in its rendering, and also forgoes linear storytelling. In other words, you have to be committed to the world in order to follow what’s going on, and even then, it might take a fair share of mental gymnastics to get each of the story points to line up. Both archaeologists by training, Erikson and Esslemont have a deep knowledge of how societies are constructed and what they leave behind. The might of empires, the fall of nations, the ways that faith and environment shape peoples over the course of ages, Malazan puts all of this into one cohesive narrative… but, like history itself, it’s unlikely that you’ll always be able to kept straight.

Buy the Book

The God Is Not Willing

The Matrix Trilogy

Sure, the first film makes everything seem pretty cut and dried, but if you’ve seen the whole Matrix trilogy, you know that things get a lot weirder. The second movie is taken up by an underground rave/orgy in the city of Zion, and a chase scene while Neo busies himself trying to find the Keymaker to the Matrix. At some point Neo discovers the ability to turn off machines using his mind? By the third film, Agent Smith has become obsessed with destroying both the Matrix and the real world (because he became a rogue program instead of allowing himself to be deleted after his defeat by Neo), and absorbs the Oracle to get precognitive powers. Neo gets blinded in the real world by one of Smith’s agents, but discovers that he can still somehow see the world in golden light. Neo meets the Architect of the Matrix and strikes a deal with him to stop Smith in exchange for peace between machines and humans. There’s a lot of chosen-y religious imagery, but it’s just kinda… there? But that doesn’t stop the films from being weirdly enjoyable.

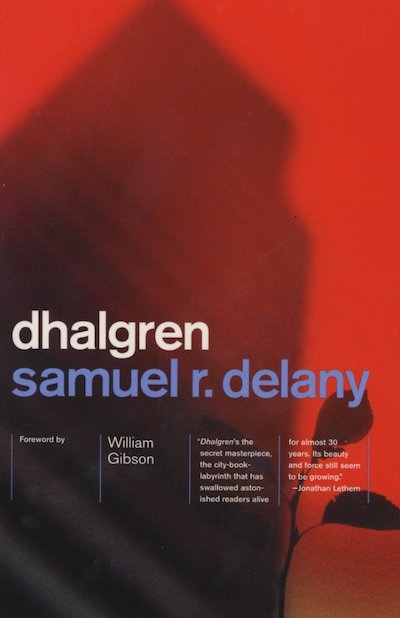

Dhalgren by Samuel R. Delany

When your protagonist can’t even remember their own name or history, pretty much anything can happen. Set in the city of Bellona, Dhalgren exposes its readers to a phantasmagoria of images and moments that stick in the mind even when their meanings aren’t quite clear. A woman turns into a tree. The sun terrorizes the populace. Two women are found reading the opening of the book itself within Dhalgren’s pages, but the story begins to diverge from what you’ve read. The title itself is a mystery—it may be the last name of a character in the book, but this is never confirmed. Like Finnegan’s Wake, the story ends mid-sentence, but can connect with the book’s opening sentence, making it a never-ending circuit. Repetition and echoes and circular imagery are part of what make Dhalgren such a unique piece of literature, and the book challenges perception as it is being read, blurring the lines of fiction and experience in a way that only Delany can deliver.

Battlestar Galactica

Okay, so Starbuck was… an angel?

Originally published April 2020.

Emmet Asher-Perrin loves stories they don’t entirely understand. You can bug them on Twitter, and read more of their work here and elsewhere.